Why were they made?

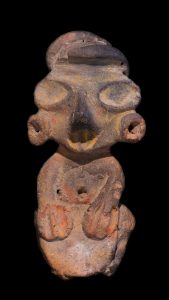

Tlatilco culture lacked writing, so thought about the purpose and use of their figurines has necessarily been speculative and circumstantial. They have been variously described as fertility figures, portrayals of secular life, and representations of shamanic trance. Since most archaeologically excavated examples were found in graves, we may assume that whatever their other uses, one of the roles of figurines was to accompany the dead.

The cross-cultural ubiquity of figurines in the ancient world, and the dominance among them of female representations, led early scholars to suggest that they were fertility figures. This school of thought reached a peak in the late 20th century with the work of Marija Gimbutas and others, who for Old Europe in particular, proposed a Neolithic matriarchy dominated by worship of a “Mother Goddess”.³

Many more recent scholars have challenged this paradigm, questioning even whether the gender concepts of ancient cultures corresponded to our own.4 Douglass Bailey of San Francisco State University has proposed that the making and manipulation of figurines may have been a way of establishing our own self-image and defining the boundaries of personhood and gender.5

Discussions of Tlatilco figurines mirror these broader trends. In 1952 Mexican archaeologist Laurette Séjourné pointed out that the predominant yellow of Tlatilco figurine painting, with highlights in red and black, mirrored the colors of corn and the costumes of later Aztec “corn maiden dancers”; she suggested that many of the figurines represented a maize goddess or young women impersonating a maize goddess and that double-faced figurines might correspond to doubled ears of corn.6

Art historian and archaeologist Michael D. Coe of Yale countered in 1966 that “Séjourné among others has suggested that they serve as fertility images to assure abundant harvests, but this does not explain the presence of male or androgynous figurines. The wide range of human activities – mothers with children, dancers, ball players, and musicians – implies a closer relation to secular life.”7

More recently, Patricia Ochoa Castillo of Mexico’s National Museum of Anthropology has suggested that the figures of musicians, dancers, acrobats and contortionists “represent shamans [using] music, dance, extreme physical exercise, and hallucinogenic consumption to reach states of ecstasy, and in the process cure a sick person, predict the future or communicate with the ancestors and the gods.”8

Ochoa Castillo points out that in addition to figurines, some Tlatilco graves contain the paraphernalia of shamanic performance, including pyrite mirrors, bone-carved piercing implements for ritual autosacrifice, fungiform ceramics and small mortars and mixing bowls for herbal preparation. The presence of double-faced and double-headed female figurines, and of many female figurines with distorted or trance-like facial expressions, also suggests the possibility of the representation of female shamanic performance.

3Gimbutas, Marija, The Gods and Goddesses of Old Europe and other books.

4Richard Lesure provides an overview of evolving scholarly theories about figurines in Interpreting Ancient Figurines: Context, Comparison and Prehistoric Art, Cambridge, 2011

5Bailey, Douglass, “Figurines, Corporeality and the Origins of the Gendered Body”, in D. Bolger (ed.) Companion to Gender Prehistory, pp. 244-64, Oxford: John Wiley, 2012

6Séjourné, Laurette,: Una Interpretación de las Figurillas del Arcaico”, Revista Mexicana des Estudios Antropológicos 13-1, 1952

7 Coe, Michael, The Jaguar’s Children: Pre-Classic Central Mexico, New York Graphic Society, 1965, p. 25

8Ochoa Castillo, Patricia, Preclásico: Museo Nacional de Antropología, Conaculta-INAH 2004, pp. 11-12