HOME| THE STORY | THE PRODUCTION | ABOUT THE MAYA SCRIPT |SCREENINGS |REVIEWS

| PRESS KIT | INTERVIEW ARCHIVES | RESOURCES | SPONSORS

Archeologist Michael D. Coe,

author of “Breaking The Maya Code”

Breaking the Maya Code was eleven years in the making. It originated with a conversation between director David Lebrun and archaeologist Michael Coe (author of the book “Breaking the Maya Code”) at the 1997 Maya Meetings at the University of Texas in Austin, and began production with extensive filmed interviews with Mayanist Linda Schele in the fall of 1997. (Schele, a central figure in the decipherment, had just been diagnosed with pancreatic cancer. She died in early 1998).

Art Historian Linda Schele.

Photo © Justin Kerr

The project gathered an advisory board including Michael Coe as

principal advisor together with epigraphers (Maya writing specialists) Federico Fahsen, Nikolai Grube, Stephen Houston, Simon Martin, Peter Mathews, and David Stuart; archeologists William Fash and the late Robert Sharer; art historians Mary Miller and Karl Taube; Maya historian George Stuart; photographer Justin Kerr; and ethnographers Barbara Tedlock and the late Evon Vogt. Many other scholars gave invaluable aid to the project over the years. A full list of project advisors, consultants and interviewees is available under credits.

Director David Lebrun at the Maya site of Cobá

in Campeche, Mexico.

Anthropologist Dennis Tedlock (left) and director Lebrun plan a route in the Guatemalan highlands.

In 1999, under a research and scripting grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities, a year of archival research was performed and over twenty audiotape interviews were conducted by director David Lebrun and a small research staff. Out of more than a thousand pages of interview transcripts, a shooting script took shape.

Detail of a carved throne excavated in 1999 at Palenque Temple 19 (Reproduction authorized by the Institutio Nacional de Antropologia e Historia, CONACULTA, Mexico).

Also in 1999, the project documented the unearthing of a stunning throne and other treasures, covered with delicate hieroglyphic inscriptions, in the ruins of Palenque’s Temple 19.

Under the non-profit sponsorship of the Precolumbian Art Research Institute of San Francisco (PARI), full production funding was eventually acquired from the National Endowment for the Humanities, the National Science Foundation, and ARTE France. Principal photography began in December 2004.

Cinematographer Steven Kline frames the palace at Palenque.

To tell the epic story of Breaking the Maya Code required shooting at over forty locations in nine countries.

In Mexico, production locations included the ancient sites of Palenque, Chicanná, Toniná, Cobá, Calakmul as well as numerous historic locations in Yucatán, site of the first Spanish conquest of the Maya

Guatemala locations included the National Museum of Archaeology and History and remote highland villages; in Honduras we spent ten days shooting at the great Maya city of Copán.

Cinematographer and lighting designer Amy Halpern with Lebrun and Kline on the acropolis at Copán.

Cinematographers Steven Kline and Amy Halpern adjust the

Panasonic SDX900 camera at Copán.

Grip-electricians Raul Salazár and Javier Guadarrama with the

equipment truck from Panavision.

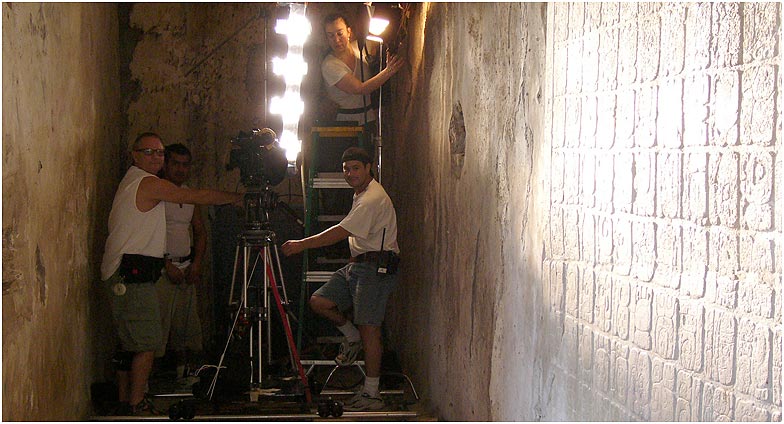

Shooting Maya stone inscriptions in remote locations presented formidable challenges. The beautiful but shallow inscriptions can virtually disappear under the shaded light of the jungle canopy or a temple interior. To bring out their beauty and detail, our intrepid electricians, Javier Guadarrama and Raul Salazár of Panavision Mexico, drove a 5-ton truck packed with lighting equipment, a dolly, dolly track and a generator from Churobusco Studios in Mexico City to all our major shooting locations in Chiapas, Campeche, Yucatán, and Honduras.

Crossing the Guatemala / Honduras border.

We dragged the 400 pound generator to the heights of Palenque’s temples and to the depths of the jungle at Cobá to light the inscriptions with raking light from banks of airport landing lights called Iride lights, a lighting tool pioneered by Director of Photography Vittorio Storaro and supplied to us by Cinelease in Burbank.

Amy Halpern lights a hieroglyphic panel in the Temple of the Inscriptions, Palenque.

Dolly shot at Chicanná

Producer Rosey Guthrie and the grips lay dolly track at Copán.

Director Lebrun adjusts the 8×10 still camera over

a carved altar at Copán.

Rather than shoot direct to video, complex Maya inscriptions and carvings were shot on 4×5″ and 8×10″ sheet film. This allowed us to capture detail far beyond the capacity of any current digital media, and to have the flexibility in post-production to move around an inscription and focus on individual hieroglyphs and other details.

A ceremony at Momostenango, in the Guatemala highlands.

With a smaller crew and a less imposing camera package, we filmed village ceremonies, interviews with Maya teachers and ceremonialists, and classrooms where the results of the decipherment are being re-integrated into Maya culture.

Students of Tuumben Saasil, a hieroglyph class in the Yucatán village of Sisbicchén greet the crew with a banner. In hieroglyphs and alphabetic letters it proclaims “A good day for you!”.

Cinematographer Halpern frames Bishop Landa’s Relación, a key document in the decipherment, in the library of the Academia Real de Historia, Madrid.

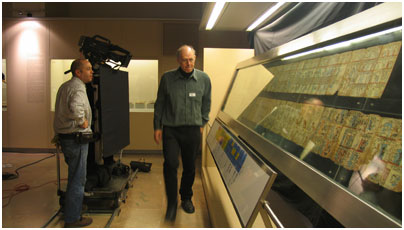

Shooting in the US, Canada and Europe included interviews with key figures in the decipherment story as well as photography in museums and archives. Locations ranged from the office on the banks of St. Petersburg’s ice-bound Neva River where a lone Russian Mayanist made a key step in the decipherment, to the libraries in Dresden and Madrid where two of the four surviving Maya books are on display.

Lighting a stela in the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology.

Lighting in the studio of Maya art photographer Justin Kerr, New York City.

Shooting on the banks of the Neva, St. Petersburg, Russia.

One of four surviving Maya books, the Madrid Codex, at the Museo de las Americas, Madrid.

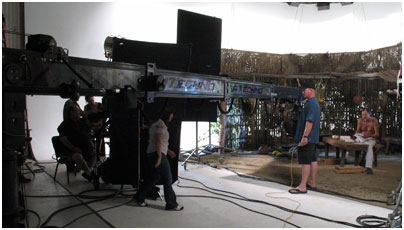

Finally, reenactment scenes were shot in the Los Angeles area. The ruins of the Berlin Library and the interior of a Maya thatched house were built on a Woodland Hills sound stage, and the interior of a nineteenth century archive was recreated from treasures in the rare book department of the Huntington Library.

Building a Maya house interior on a Panavision sound stage.

Shooting the Maya interior with a Panavision Technocrane.

Back at Night Fire Films in Los Angeles, over 100 camera tapes were input into our Final Cut Pro editing system, eventually straining the capacity of our 1.6 terabyte RAID drive.

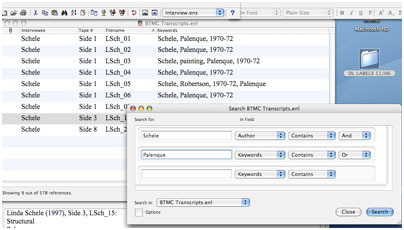

Searching in Endnote for Mayanist Linda Schele’s interview comments on Palenque.

More than two dozen extensive interviews were transcribed. Hundreds of potentially usable interview selections were entered into the bibliographic database program EndNote, and keyed to one or more of over two hundred key words (people, places, dates, events and other themes). This invaluable technique enabled us, throughout the editing process, to perform searches for relevant interview quotes based on their relevance to single or multiple criteria. (This material is available to researchers in the Interview Archives section of this web site.)

As editing proceeded, over 300 animated and graphic sequences were also taking shape. Calligrapher Mark Van Stone created hundreds of drawings of glyphs and other details. Graphic designer Charles Owens shaped Mark’s drawings and other materials into dozens of animated sequences illustrating the inner workings of the Maya script.

Animation showing 19th century decipherment of the glyphs for Maya gods.

3-D animation of the Maya calendar.

Meanwhile graphic artists Bernadette Rivero, Kim White, Daryl Furr, Nik Blumish and Jim Bromley applied digital highlighting to high resolution scans of our 2 ¼, 4×5 and 8×10 stills. These were then incorporated into Adobe After Effects projects in which the “camera” moves through complex inscriptions as individual glyphs and iconographic details are illuminated one by one.

Digital highlighting brigs out the details of Lord Chan Bahlam making an offering on the Tablet of the Foliated Cross, Palenque

(Reproduction authorized by the Institutio Nacional de Antropologia e Historia, CONACULTA, Mexico).

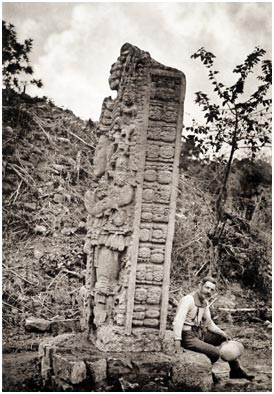

Early photograph by Alfred Maudslay of a stela at Copán.

An extensive search for archival materials made use of the local facilities of the Getty Research Institute and the UCLA Graduate Research Library, and of dozens of other archives worldwide. (A full list of archival sources is available under Credits).

Eventually hundreds of rare photographs and video clips were sent to us from all over the world, scanned or copied, and returned.

Finally, all these elements were output or uprezzed to 1080i high definition HD at the Hollywood post facility Digital Film Tree, and brought together with CCH Pounder’s narration, Yuval Ron’s original score and George Lockwood’s sound design.

Painting of Piedras Negras by Mayanist Tania Proskouriakoff, photographed at the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology archives.

We finished at the end of February and premiered the film two days later at the 2008 Maya Meetings in Austin, where the project had its beginnings 11 years before.